Wrapping Up 2024: The Year of Safety in Design in Australia

Wrapping Up 2024: The Year of Safety in Design in Australia

As the sun sets on 2024, it’s time to buckle up (safely, of course) and take a joyride through the latest news, events, and developments in safety in design across Australia. This year, we’ve seen progress, innovation, and, yes, a few cringe-worthy moments that made us wonder if some folks skipped Safety 101. So grab your hard hats and reflective vests – let’s dive into the good, the bad, and the “oh no” of 2024.

What Is Safety in Design, Anyway?

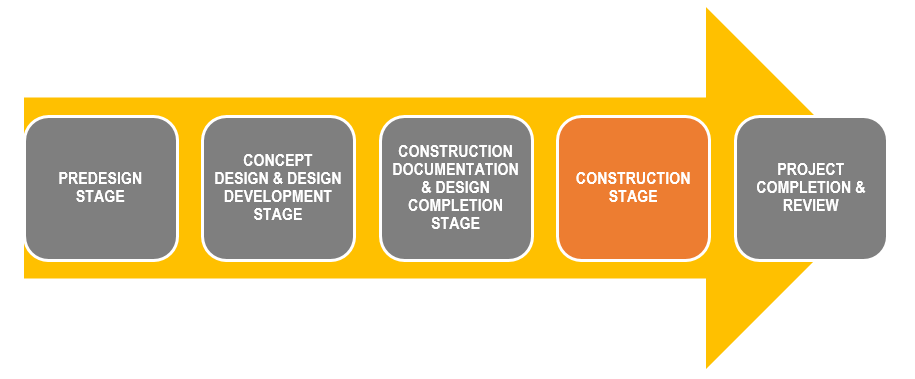

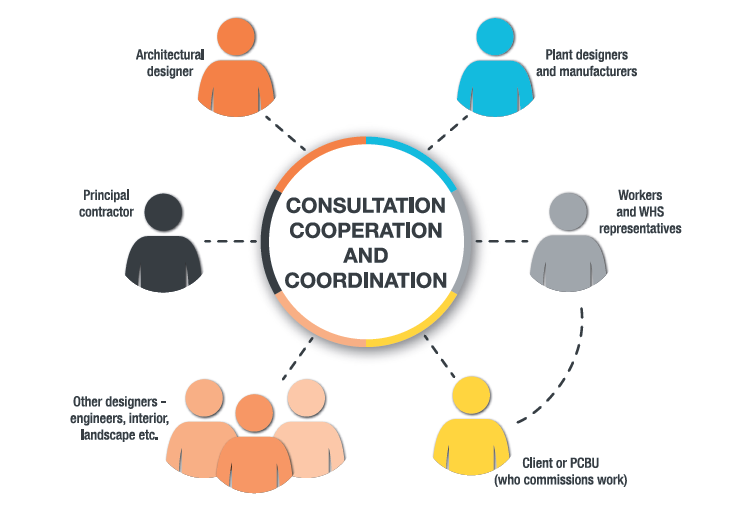

For the uninitiated, safety in design (SiD) is the practice of incorporating safety measures into a product, building, or system’s design to eliminate risks before they manifest. It’s not just about ticking boxes; it’s about preventing injuries, reducing costs, and ensuring that the world we live and work in is as safe as possible.

Now, on to the highlights of 2024!

What’s Been Achieved in 2024?

1. Widespread Adoption of Safe Design Practices

Australia stepped up its game in 2024 with an impressive adoption of safe design principles across multiple industries. Whether it’s urban development, construction, or product manufacturing, SiD has become less of an afterthought and more of a forethought.

Key Wins:

- Legislation: Protecting people and the planet just got a boost with two key regulatory upgrades that consider the lifecycle impact of decisions made at the design stage: WHS amendments on materials with over 1% crystalline silica and NSW’s Hazardous Chemicals Act. They enforce stricter controls on the usage of construction materials and hazardous chemicals (in many construction materials), safeguarding the health of installation workers, users, those exposed during deconstruction or disposal AND our (currently only) planet’s environment.

- Product Design: Consumer goods – from electric scooters to kitchen appliances – saw a rise in ergonomic and safer designs.

- Tech Innovations: Augmented reality (AR) tools for risk assessment allowed teams to visualize and mitigate hazards before breaking ground.

Safe design is no longer a niche practice but an integral part of the design process. And the cherry on top? It’s saving lives and money – a rare win-win in any industry.

2. The “No Excuses” Year for Compliance

Regulators weren’t playing around this year. Safe Work Australia introduced more stringent SiD guidelines, leaving little room for “creative interpretations” of safety standards.

Memorable Moments:

- New South Wales expanded the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 and the Residential Apartment Buildings Act 2020, enforcing stricter compliance and safety standards during the design and construction phases, including more regulation on preventing the incorporation of hazardous materials.

- Several high-profile fines served as wake-up calls, with construction firms and developers hit with $1million+ penalties for ignoring design-phase risk assessments. Ouch.

- Online SiD training programs saw a record 25% increase in enrolments, signaling a tipping point where people are getting that compliance with SiD at the design stages is the path of least resistance and maximum scope for creative safety implementation.

Takeaway: compliance workshops are waaaay more enjoyable than a court date.

3. Safety in Design Extends to Our Digital World

The Australian government has announced a push to expand Safety in Design principles into the digital realm, emphasizing the responsibility of online platforms to safeguard users. “Digital businesses would be required to take reasonable steps to prevent foreseeable harms on their platforms and services. The duty of care framework would be underpinned by risk assessment and risk mitigation, and informed by safety-by-design principles” announced Communications Minister Michelle Rowland.

Improving safety on online platforms is to be considered in the inherent design of these platforms, emphasizing that a duty of care exists for digital businesses, requiring them to take proactive steps to mitigate foreseeable harms on their platforms and services.

The framework, grounded in risk assessment and mitigation, aims to embed user safety and rights into the core of online product and service development. While the exact timeline for introducing this legislation to Parliament and details of penalties remain unclear, industry leaders have expressed support for upholding Safety by Design standards to enhance digital safety for Australians.

The eSafety Commissioner is now a Safety in Design fan: digital platforms must move from an anything goes “move fast and break things” approach to maximising profit, and put user safety and rights at the centre of the design and development of online products and services from the design stage forward.

Where We Still Need Work

Despite the strides made this year, not all is smooth sailing. Here are a few areas that still need some elbow grease:

1. Small Businesses: The Stragglers

Many small businesses continue to lag in implementing SiD practices, often citing cost or lack of awareness as barriers.

Challenges Faced:

- Limited access to affordable training programs.

- A “She’ll be right” attitude – Australian as Vegemite, but sniffed at as an excuse for non consultation and consideration, no matter your budget.

It’s time to bring small businesses into the fold with targeted incentives and support – because safety is everyone’s business. Recognizing that smaller design practices often face cost barriers, Safe Design Australia has offered self-paced safety in design awareness courses for over six years, including our flagship “THE NOT BORING Safe Design Course.” These courses have been augmented over time, with several new programs optimized for CPD accreditation planned for 2025. Our flagship “THE NOT BORING Safe Design Course” remains Australia’s favorite, offering a cost-effective and time-efficient training experience that delivers value – and dare we say, a chuckle or two along the way. Definitely not boring. Learn more or enroll here: THE NOT BORING Safe Design Course.

2. Residential Construction: Cutting Corners

The residential construction sector had its fair share of mishaps in 2024, with a noticeable uptick in structural defects (and potentially gajillions of $’s in repairs slated) due to corner cutting and under-whelming safety in design consideration given to residential projects.

Case in Point:

A Sydney apartment complex made headlines after cracks appeared in its foundation just six months post-completion. Investigations revealed cost-cutting measures during the Opal Towers design phase as the culprit.

Spoiler: lawsuits are expensive.

3. Digital SiD: A Mixed Bag

While AR and AI tools are being embraced in larger firms, smaller players are struggling to adopt these technologies due to cost and lack of expertise.

Missed Opportunities:

Digital SiD tools have the potential to democratize safety planning, but without widespread access, they risk becoming tools of the elite.

The Future of Safety in Design

Looking ahead, the SiD landscape in Australia promises continued evolution. Here’s what we can expect:

1. More Regulations (and That’s a Good Thing)

Love them or hate them, more relevant regulation is likely to ensure that safety becomes second nature for everyone – not just the big players, and not just designers of structures. Watch out for updates to the National Construction Code in 2025 and development of Safe Design legislation around the eSafety digital framework.

2. Inclusivity in Safe Design

From wheelchair-accessible spaces to age-friendly housing, the next frontier in SiD is inclusivity. Designing for all abilities isn’t just ethical – it’s smart business.

3. Green Safe Design

Sustainability and safety are increasingly intersecting, with designs that protect both people and the planet. Think recycled materials, energy-efficient systems, and carbon-neutral construction methods.

Conclusion

As we wrap up 2024, it’s clear that Australia is making great strides in safety in design. From industry-wide adoption of safe practices to innovative projects that set new benchmarks, the progress is undeniable. However, challenges remain, especially for smaller businesses and residential construction.

With collaboration, innovation, and a dash of humor, there’s every reason to believe 2025 will be even safer (and maybe a little more fun). So here’s to another year of building smarter, safer, and better for everyone.

Until next year, stay safe and keep designing!

SEO Keywords: Safety in Design Australia, 2024 safety trends, Safe Work Australia, construction safety, ergonomic design, green design, AR safety tools.